In the News

Read news features about LEAP, anosognosia, and the impact of this methodology on mental health. From personal stories to expert analyses, uncover innovative approaches to understanding and addressing this condition. LEAP is also featured in other applications, including business and politics.

LEAP, Anosognosia Articles

Experts in schizophrenia research and treatment offer glimpses of the future.

Schizophrenia Today: What's New and What's ComingRob Dart has spent a year on the streets believing people are trying to control him via hypnosis.

A Lawyer’s Slide Into Psychosis Was Cap… Profile. He Tells Us His Story. – WSJSan Luis Obispo County is setting up a Care Court program to help people suffering from mental illness who need behavioral health services.

article_In a crisis people with mental illness have few options beyond arrest Can CARE Court help_Tribune June 2024Read more at: https://www.sanluisobispo.com/news/health-and-medicine/article287561525.html#storylink=cpy

INFLUENCE

Using LEAP in Business: Practical Tips for Overcoming Resistance

by Mark Goulston

Although many managers and leaders are under pressure to get things done quickly, pressuring subordinates frequently leads to resistance. This is not due to stubbornness as much as it is due those subordinates simply feeling overwhelmed by the volume of work they have. Emotions also come into play; for instance, if you’re trying to get through to an irate customer or shareholder, it can be tough to break through the resistance their anger creates.

To get some tips on how to overcome resistance I reached out to Xavier Amador, originator of the LEAP Method (LEAP stands for Listen-Empathize-Agree-Partner) and Founder of the LEAP Institute and author of I’m Right, You’re Wrong, Now What? Break the Impasse and Get What You Need.

MG: Dr. Amador, or shall I call you, Xavier, how did you come up with the idea that we needed a more effective way of overcoming resistance than the usual pushy/persuasive approach?

XA: Mark please call me Xavier. Okay if I call you Mark?

MG: Of course!

XA: Before answering your question, I want to point out something that just happened. By asking me what name I prefer you call me by, you took a step toward connecting with me and not creating resistance — You did this before we were even out of the gate! I practice the same simple habit with almost everyone. Without asking, you didn’t know if I would find “Dr. Amador” too formal and distancing, or “Xavier” too presumptuous and disrespectful. Either reaction would have raised a little resistance. And the fact that you pronounced my name correctly — “Javier” instead of “Zavier” — helped too. You obviously took the trouble to find out, or saw me speaking, and remembered the pronunciation. So without hearing one word from me you were already listening. And that’s the cornerstone to lowering resistances.

Now to your question: I would love to say the idea was mine, but it’s actually ancient wisdom and the result of paying attention to what actually works. The lesson learned is: You don’t win on the strength of your argument. You win on the strength of your relationship. And you can strengthen relationships in seconds and easily by putting down your rusty overused communication tools and picking up some new ones. Feedback from thousands of LEAP followers who are company owners, CEO’s, managers and sales reps reinforced the universality of this vital lesson I learned years ago working with psychotic patients who were literally living in an alternate universe: it feels [like] “What planet is he on?” when someone gives us a reflexive no and resists what is obviously common sense.

You never win on the strength of your argument — or your negatively perceived directive if you are the one holding power in the relationship. Even if your subordinate does what you wanted, the initial resistance will fester and spread as they implement the details. If it was pushed down their throats, instead of something they felt some ownership of, they will resist…[and] it will come back to bite you later. What we hear over and over again is this:

“When I stopped trying to convince her and instead focused on listening to his point of view and respecting it, the resistance just disappeared. It happened so fast it felt like magic!”

MG: Why do so many people especially managers and leaders approach resistance in such an ineffective manner?

XA: Because its natural to punch back. It’s a lifelong habit most people have. We repeat ourselves, often more loudly and over and over again, when someone hasn’t heard or doesn’t agree. When I have a good idea, a solution to a problem, or a product/service I know will increase market penetration, I am eager to communicate it to the other person or group. And when I get resistance, it feels like I’ve been pushed back or hit. And so the reflex is to push or hit back — to counter punch in an effort to show the other side why they were wrong. The reflex is to stand my ground.

This type of interaction looks just like a boxing match. Using LEAP we’ve learned you can stand your ground without verbally hitting back. Here’s the first and most important tool:

When you get resistance, [say to yourself], “Shut up, listen and win!”

That’s what I say to myself to remember to use the tools I know work. “Shut up” may sound rude and counter productive, but for me it’s a splash of cold water. It gets my attention so I can stop dismantling and start using my authority to build stronger relationships. That’s the prize, a strong relationship. Strong relationships are the key to meaningful and effective partners and work relationships. Nothing else comes close to being as important. No productive business can exist without strong relationships — think about it. And yet, too often, we ignore the “state of the union” while resistance, defensiveness and even tempers are on the rise.

Now that you’ve stopped talking, to show you listened, repeat back what you’ve heard “So you don’t think this will work and it’s a bad idea because…. Did I get that right?” Just listen and make sure you’ve heard it the way the other person meant it. Then explore just a little bit more. Go for the emotion behind the push back. Empathize.

[Say something like,] “Now that I understand your position, I can see why you would be uneasy buying in.” Take the resistance that is negative energy and use it, by absorbing it, so the person feels respected and safe, lowers their defenses, and as a result opens up to you.

In this exchange, instead of boxing, the verbal interaction looks more like Jujitsu. You meet the resistance, not with a push or punch but instead with open hands. As the person comes at you with their resistance, with open hands you step aside and embrace the negative movement, use its energy, to move the person where you want them.

MG: What would you say to those who may feel that “lowering their guards” and leading

with “open hands” will undermine their authority?

XA: Well first I would listen to their resistance and lower it by communicating my genuine understanding and empathy for it. With authority comes strength. You can use that strength to strengthen the relationship or to strong-arm the other person and create a resistance movement in your own backyard.

You have the luxury of being able to speak softly knowing that you are the one carrying much bigger stick.

Here’s a life and death example of this principle. LEAP-trained hostage negotiators have far superior firepower when they’ve cornered the person they’re trying to persuade, but they approach their subject with an open ear and open hands “Talk to me, tell me what you want?” is what works to engage someone who has taken hostages, and to convince them to release their hostages and come with you peacefully. “Come out with your hands up we have you surrounded and out-gunned,” leads to a fire fight. Don’t help others hold your ideas, proposals and directives hostage with their resistance by opening fire.

MG: I don’t know if this is an example of Partnering with you, or just showing good manners, but Xavier I’d like to give you the final word. Do you have a quote or statement that will help remind our readers of the importance of LEAPing into better communication rather than jumping down people’s throats when they are resistant?

XA: I will repeat myself because the following two things are that important. First, if you are getting push-back, shut up, listen and win. And second, remember when you are faced with resistance you never win on the strength of your argument, you win on the strength of your relationship. One final word, I hope your readers will let me know if our conversation helped them by contacting me at XavierAmador@LEAPinstitute.org or visit LEAPinstitute.org. Thanks Mark for the opportunity to have this conversation.

Mark Goulston, M.D., F.A.P.A. is a business psychiatrist, executive advisor, keynote speaker, and CEO and Founder of the Goulston Group. He is the author of Just Listen (Amaxom, 2015) and co-author of Real Influence: Persuade Without Pushing and Gain Without Giving In (Amacom, 2013).

God Knows Where I Am

By Rachel Aviv

Diagnosed as bipolar, Linda Bishop used her hospital stay “to prove that I don’t have a mental illness (and never did).”

A tall, athletic fifty-one-year-old with blue eyes and a bachelor’s degree in art history from the University of New Hampshire, Linda had been admitted to the hospital in late October, 2006, after having been found incompetent to stand trial for a series of offenses. She spent most of her eleven months there reading, writing, and crocheting. She refused all psychiatric medication, because she believed her diagnosis (bipolar disorder with psychosis) was a mistake. Each time she met a new psychiatrist, she declared her lack of respect for the profession. Only when conversations moved away from her mental illness, a term she generally placed in quotation marks, was she cheerful and engaged. Her medical records consistently note the same traits: “extremely bright,” “very pleasant,” “denies completely that she has an illness.” In the weeks leading up to her discharge, her doctors urged her to make arrangements for housing and follow-up care, but Linda refused, saying, “God will provide.”

During a rainstorm on her fourth day out of the hospital, Linda broke into a vacant farmhouse for sale on Mountain Road, a scenic residential street. The three-story home overlooked a brook and an apple orchard, and a few rooms were still sparsely furnished. Linda intended to stay only a few nights, but she began to worry that her dirty clothes would attract attention if she walked back to town. “I look terrible . . . like a vagrant,” she wrote in a black leather pocket notebook that the previous tenants had left behind. Linda had led a nomadic existence ever since she had abandoned her sleeping thirteen-year-old daughter, in 1999, leaving a note saying that she was going to meet the governor. She drifted between homeless shelters, hospitals, and jail. She wrote in the journal that she wasn’t ready to “make my presence known—and just start the whole mess again—to prove what—that I’m all right? Have done that too many times.” Two days after breaking into the house, she decided to make the place her temporary home. She would subsist on apples while “awaiting further instructions” from God.

Linda settled into a routine. In the morning, when the sun poured through the living-room window, warming the end of the couch, she read college textbooks she found in the attic. The former tenant appeared to have dropped out of school in 1969 (“but his creative writing is very good!” she noted), and she began embarking on the education he had abandoned. She began with Joseph Conrad and moved on to biology (“chloroplasts, lysosomes, mitochondria + cell division!”) and “Great Issues in Western Civilization.” When she had enough energy, she did her “chores.” She combed her graying brown hair—first with a small rake, and, when that proved too cumbersome, with a fork—and tidied the house, in case potential buyers came for a viewing. There was no electricity or water, but, after dusk, she rinsed her underwear in the brook, collected water with a vase, and picked apples.

After the first week, she estimated that she had lost ten pounds. When she looked in the mirror, she was startled by how drawn her face had become. Yet after enduring so many irritations in her hospital unit—patients who wouldn’t stop talking, or who touched her, or sat in her favorite chair, or made noise in the middle of the night—she didn’t mind having time alone. From her windows, she enjoyed watching purple finches, tufted titmice, chickadees, and “Mr. and Mrs. Cardinal.” She wished she had binoculars. A neighbor came over to mow the lawn and pull the weeds. “He has no idea I’m here!” Linda wrote, as she watched him from an upstairs window.

The threat that Linda was hiding from was a shifty one—she alluded to conspiracies involving her older sister, the government, and Satan’s workers—but she also wondered if anyone was even looking for her. She kept retracing the series of events that had led her to this house. She knew it didn’t “make sense to be barely existing”—she got light-headed just walking up the stairs—but she felt that the situation must have been willed by the Lord. By the end of October, she had a stash of three hundred apples. She worried about the coming winter as she watched trees lose their leaves, milkweed seeds blow in the wind “like it’s snowing,” and geese migrate south. Still, she could find “no signs or clues that I should be doing anything different.”

Throughout Linda’s stay at New Hampshire Hospital, her doctors routinely noted that she lacked “insight,” a term that has a troubled legacy in psychiatry. Studies have shown that nearly half of people given a diagnosis of psychotic illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, say that they are not mentally ill—naturally, they also tend to resist treatment. The psychiatrist Aubrey Lewis defined insight in 1934 in the British Journal of Medical Psychology as the “correct attitude to a morbid change in oneself.” But the definition was so ambiguous that his paper was ignored for over fifty years. Psychiatrists were reluctant to move away from objective, observable phenomena and to examine the private ways that people make sense of the experience of losing their minds. Today, insight is assessed every time a patient enters a psychiatric hospital, through the Mental Status Examination, but this form of awareness is still poorly understood. Patients are considered insightful when they can reinterpret unusual occurrences—growing angel’s wings, feeling as if their organs have been removed, decoding political messages in street signs—as psychiatric symptoms. In the absence of any clear neurological marker of psychosis, the field revolves around a paradox: an early sign of sanity is the ability to recognize that you’ve been insane. (A “correct attitude,” for most Western psychiatrists, would exclude interpretations featuring spirits, demons, or karmic disharmony.)

Getting patients to acknowledge their own disorders also has become an ethical imperative. Implicit in the doctrine of informed consent is the notion that before agreeing to take medication patients should be aware of the nature and course of their own illnesses. In balancing rights against needs, though, psychiatry is stuck in a kind of moral impasse. It is the only field in which refusal of treatment is commonly viewed as a manifestation of illness rather than as an authentic wish. According to Linda’s treatment review, her most perplexing behavior was her “continuing denial of the legitimacy of her ‘patienthood.’ ”

When psychoanalytic theories were dominant, patients who claimed they were sane were thought to be protecting themselves from a truth too shattering to bear. In more recent years, the problem has been reframed as a cognitive deficit intrinsic to the disease. “It has nothing to do with willfulness—you just don’t have the capacity to know,” Xavier Amador, an adjunct professor of psychology at Columbia University’s Teachers College, said. Amador is the author of the most widely used test for measuring insight, the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder, which asks patients why they think their judgments or perceptions have changed. Although researchers haven’t uncovered distinct neurological anomalies linked to lack of insight, Amador and other scholars have adopted the term “anosognosia,” which more typically describes patients with brain damage who lose the use of limbs or senses yet cannot acknowledge the existence of their new disabilities. Those who go blind because of lesions in their visual cortex, for instance, insist that they can still see, and tell fanciful stories to explain why they are walking into furniture.

Anosognosia was introduced as a synonym for “poor insight” in the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, but the concept remains slippery, since the phenomenon it describes is essentially social: the extent to which a patient agrees with her doctor’s interpretation. For Linda, the validity of her diagnosis was the subtext of nearly all her encounters with her psychiatrists, whose attempts to teach her that parts of her personality could be “construed as a mental illness,” as she described it, only alienated her. She wrote to a friend that she was using her hospital stay as an opportunity “merely to prove that I don’t have a mental illness (and never did).”

Linda had always been fond of farmhouses. She grew up on Long Island and took pride in her family’s sprawling vegetable garden. “My childhood was a good one, with loving and supportive parents who believed in doing things as a family,” she wrote in an application to an assisted-housing program. She had a large circle of friends and excelled in school with little effort. “She was bubbly and exuded competence,” an old friend, Holliday Kane Rayfield, who is now a psychiatrist, said. Linda’s family thought she would become a professor, but she never settled on a professional career. Kathleen White, her closest friend from college, said that her “dream was to find a guy with a sense of humor, have kids, and live on a farm.”

Linda got married in 1985, and gave birth to her daughter, Caitlin, five months later. But she complained about her husband’s temper, and after her brief marriage ended she struggled to support Caitlin on her own. She worked long hours at a Chinese restaurant in Rochester, New Hampshire, and on her days off she and Caitlin visited museums in Boston or went on camping trips or took aimless drives through the state. Caitlin, now a twenty-five-year-old photo technician at Walmart, told me, “We were each other’s world.” It wasn’t until her mother quit her waitressing job in order to evade the “Chinese Mafia” that Caitlin, who was in seventh grade, began to doubt her mother’s judgment. In 1999, in a purple Dodge Dart, the two fled the state, heading toward Canada. Caitlin, too, was terrified of being captured. “I figured I was collateral damage,” she said. Linda called friends on the way but lied about her location, because she suspected that she was talking to spies. While her mother used pay phones at gas stations, Caitlin waited in the car. “At some point, I just thought to myself, I know better than this,” she said.

When they returned, a little more than a week later, after Linda’s fears had subsided, Linda’s sister, Joan Bishop, and their parents tried unsuccessfully to persuade Linda to see a doctor. Soon, she disappeared again. She went to Concord, the state capital, to inform authorities that the government was behind John F. Kennedy, Jr.,’s plane crash, and then wandered alone through the state for several days, feeling as if she had “ingested some sort of poison or drug without knowing it.” Caitlin moved in with her paternal grandmother and stayed there even when Linda came home. Linda finally checked into a hospital in Dover, New Hampshire, where she was given a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and began taking Zyprexa, an antipsychotic, and lithium, a mood stabilizer. (Her diagnosis shifted between bipolar and schizoaffective—a mixture of schizophrenia and a mood disorder—depending on the doctor.) Psychotic disorders typically begin in early adulthood, but it is not uncommon for them to develop later in life, particularly after periods of stress or isolation. Linda sobbed for the first few days, and talked about how betrayed she felt by those who were scheming against her. By the fourth day, though, her psychiatrist wrote, “She now has insight into the fact that these are paranoid delusions, and a part of her is able to say that maybe some of these things didn’t happen, perhaps some of the people she felt were plotting against her really weren’t.” Ten days later, she was released.

It was the beginning of a persistent and common cycle. With each hospitalization, Linda was educated about her illness and the need for medication. This is the standard approach for increasing insight, but it does not account for the fact that people’s beliefs, even those which are wildly false, shape their identities. If a person goes from being a political martyr to a mental patient in just a few days—the sign of a successful hospital stay, by most standards—her life may begin to feel banal and useless. Insight is correlated with fewer hospital readmissions, better performance at work, and more social contacts, but it is also linked with lower self-esteem and depression. People recovering from psychotic episodes rarely receive extensive talk therapy, because insurance companies place strict limits on the number of sessions allowed and because for years psychiatrists have assumed that psychotic patients are unable to reflect meaningfully on their lives. (Eugen Bleuler, the psychiatrist who coined the term “schizophrenia,” said that after years of talking to his patients he found them stranger than the birds in his garden.)

With medication as her only form of treatment, Linda was unable to modify her self-image to accommodate the facts of her illness. When psychotic, she saw herself as the heroine in a tale of terrible injustice, a role that gave her confidence and purpose. After the World Trade Center attacks, in 2001, she moved to New York City, because she felt she had been called to offer her help. A December, 2001, article in the New York Post, “Homeless ‘Angel’ a Blessing at Ground Zero,” described how Linda patrolled the perimeter of the site, waving an American flag, greeting visitors, and giving impromptu tours. “Angels come to earth in disguises—some come as paupers,” a construction worker was quoted as saying. A man identified as a 9/11 victim said that “God rested on her shoulder.” Linda thanked workers at the site for their efforts and talked to tourists about what they were witnessing. “I try to help people understand the enormity,” she told the reporter. She dubbed herself the head of Hell’s Chamber of Commerce.

For the next few years, Linda wandered: she lived on the streets, in homeless shelters, and in her sister’s house, on the condition that she take medication. Joan, who works as the director of education for the New Hampshire Supreme Court, has the same warm, jovial manner as her sister, and the two spent much of their free time together, though Linda’s goal was to find her own home. In 2003, she entered a supported-housing program in Manchester, New Hampshire, and told her caseworker that she wanted to “live like an adult again.” She was upset that her illness had alienated her daughter and friends. Joan told me that “Linda would talk analytically about how it had felt to be delusional. It wasn’t a matter of imagining. It wasn’t as if she felt she was being chased by government agents. In her mind, they were as real as I am right now.”

In the summer of 2004, Caitlin, by then a senior in high school, decided to move back in with her mother for the first time in five years. Their new apartment, in Rochester, New Hampshire, became the preferred hangout spot for her friends. “She was the cool mom,” Jessica Jamriska, a close friend of Caitlin’s, said. “She had stopped talking about the government, except maybe if there was an election. And the only reason she quoted the Bible is if we were having intellectual debates about, you know, whether it’s a book of morals or not.”

Linda enjoyed cooking large meals for Caitlin’s friends, but over time the stories she told at the dinner table became harder to follow. “At first, we just thought, O.K., it’s normal to have some fantasies and dreams,” Jessica said. “She would talk a lot about some dude she loved who was going to make everything all right, and we weren’t even sure he existed.”

Caitlin and Joan urged Linda to take her medication, but she said that she felt perfectly fine and complained that the drugs made her lethargic and caused her to gain weight. (Linda’s parents, who had encouraged her to follow her doctors’ advice, had died, both of them from cancer, in 2003 and 2004.) Caitlin and two of her friends finally decided to make an audiotape of Linda ranting. “We wanted to have proof, to say, look, this is objectively crazy, and someone needs to help her,” Caitlin said. They recorded her talking about how children should be armed with AK-47s, and called the police, but Caitlin said that their complaint was never taken seriously. In February, 2005, Linda’s car flipped on its side on Rochester’s main street. When the police arrived, they smelled alcohol on her breath. She said that she had purposely caused the accident, to prove “that police officers are ‘illegal.’ ”

Although it was a relatively minor offense (her alcohol level was below the legal threshold), Linda refused to pay the five-hundred-dollar bail, so she was sent to the Strafford County House of Corrections, in March. (Nationally, a quarter of jail inmates meet the criteria for a psychotic disorder.) After her first arrest, Linda threw a cup of urine at a corrections officer and struck a man with a broomstick. Joan wrote to the police department’s prosecuting attorney, explaining that before her illness Linda had never been “violent or aggressive towards anyone or anything.” She said that the family hadn’t been able to get Linda into psychiatric treatment, and asked the attorney to help.

Joan’s request led to competency evaluations, and, as Linda waited in jail for the results, she moved even farther away from the life she had led before her illness. She considered herself a “people person”—she made Christmas cards for other inmates out of lunch bags and magazine ads, sealed with grape jelly—but she found herself isolated from all the people with whom she had once been close. She wrote Caitlin long letters with tips about what cosmetics to wear, how to get a job, shop for bargains, lose weight, make apple pie, and avoid the presence of people who belong in Hell, but Caitlin stopped responding.

After a year and a half in jail, Linda was deemed incompetent to stand trial and was transferred to New Hampshire Hospital for a commitment term of up to three years. She was humiliated by the idea of anyone evaluating her competence and wrote to Caitlin, “My constitutional rights have been ignored, trampled on and violated due to your Aunt Joan.”

New Hampshire Hospital was established, in 1842, as a kind of utopian community, a reprieve from the disorder of the outside world. The hospital’s early leaders tried to help patients regain their common sense—in the first year, more than a quarter of admitted patients suffered from an “overindulgence in religious thoughts,” with several claiming to be prophets—by immersing them in a model society. The hospital was situated on a hundred and seventeen acres, and patients lived in a stately, red-brick Colonial building with a steeple and a tiered white porch, surrounded by trees. They farmed, gardened, and cooked together; there was a golf course, an orchestra, a monthly newspaper, dances, and boating on the hospital’s pond. In 1866, the hospital’s superintendent described psychosis as a “waking dream, which, if not broken in upon, works mischief to the brain,” and wrote that the goal of treatment was to “interfere with this world of self—scatter its creations and fancies and people it with objects and thoughts foreign to its own.”

As the patient population expanded, though, the hospital couldn’t maintain its early idealism. Psychiatrists no longer had time for the benevolent form of care known as “moral treatment.” As of 1936, the hospital had sterilized a hundred and fifty-five patients, and later it began experimenting with newfangled remedies, like electroconvulsive therapy and insulin-induced comas; the shock of such procedures, it was thought, might clear patients’ minds. By the nineteen-fifties, the hospital’s population had swelled to twenty-seven hundred patients, and doctors were less concerned with creating a sense of community than with maintaining security. Patients spent so many years in the hospital that they no longer knew how to leave it. (The institution has two graveyards for people who died in its care.) The hospital’s crowded wards resembled those studied in Erving Goffman’s 1961 book, “Asylums,” which showed how, through years of institutional life, people lost their identities and learned to be perfect mental patients—dull, unmotivated, and helpless.

The idea that mental illnesses were exacerbated, even caused, by the measures designed to treat them was elaborated by many scholars throughout the sixties. Thomas Szasz, a psychiatrist and prolific author, described mental illness as a “myth,” a “metaphor.” The psychiatrist R. D. Laing called it a “perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world.” In 1963, President Kennedy (whose sister Rosemary had received a lobotomy which left her barely able to speak) passed the Community Mental Health Centers Act, which called for psychiatric asylums to be replaced by a more humane network of behavioral-health centers and halfway homes. His “bold new approach,” as he called it, was plausible because of the recent development of antipsychotic drugs, which seemed to promise a quick cure. In the years that followed, civil-rights lawyers and activists won a series of court cases that made it increasingly difficult for patients to be treated without their consent. In 1975, the Supreme Court ruled that the state may not “fence in the harmless mentally ill.” Four years later, in Rogers v. Okin, a federal district court decided that involuntary medication was unconstitutional, a form of “mind control.” The court maintained that “the right to produce a thought—or refuse to do so—is as important as the right protected in Roe v. Wade to give birth or abort.”

Deinstitutionalization was a nationwide social experiment that did not go as planned. Overgrown hospitals were shut down or emptied, but many fewer community centers were opened than had been proposed. Resources steadily declined; in just the past three years, $2.2 billion has been cut from state mental-health budgets. “Wishing that mental illness would not exist has led our policymakers to shape a health-care system as if it did not exist,” Paul Appelbaum said in his 2002 inaugural address as president of the American Psychiatric Association. Today, there are three times as many mentally ill people in jails as in hospitals. Others end up on the streets. A paper in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which examined the records of patients in San Diego’s public mental-health system, found that one in five individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia is homeless in a given year.

New Hampshire Hospital, which now has only a hundred and fifty-eight beds, admits people who have been sent from jail or who pose a danger to themselves or others. Often, people arrive at the emergency room, with concerned relatives and friends, but they are turned away, because they are not an imminent threat. “Clinically, it’s a shame,” Alexander de Nesnera, the hospital’s associate medical director, told me. “These are people who may be making choices they would never have made when they were healthy. But then there’s the civil-libertarian argument: Who are we to say that they don’t have the right to change their opinions?”

Freedom often ends up looking a lot like abandonment. Tanya Marie Luhrmann, a Stanford anthropologist, told me that “there is something deeply American about the force of our insistence that you should be able to ride it out on your own.” Luhrmann has followed mentally ill women in Chicago through what is known as the “institutional circuit”—the shelters, halfway homes, emergency rooms, and jails that have taken the place of mental asylums. Many of the women refused assisted housing, because to gain eligibility they had to identify themselves as mentally ill. They would not “formulate the sentence that psychiatrists call ‘insight,’ ” Luhrmann said. “ ‘I have a mental illness, these are my symptoms, and I know they are not real’—the whole biomedical model. To ask for this kind of help is to be aware that you cannot trust what you know.”

Healthmonitor – When A Loved One Won’t Listen

Dr. Xavier Amador’s strategies for helping family or friends with mental illness.

By Maria Lissandrello

Psychologist Xavier Amador, author of I Am Not Sick. I Don’t Need Help!, knows what it’s like. For years, he struggled in vain to get through to his older brother, Henry, who was suffering with schizophrenia. And then, at last, he had an “aha” moment that allowed the barriers to fall away and opened the door to healing.

Here, Dr. Amador—you’ve seen the forensic psychology expert on CNN, NBC and elsewhere talking about cases such as the Unabomber and the Elizabeth Smart kidnapping—opens up about his personal story, and how it led to the founding of the LEAP Institute, a communication strategy that can help anyone move beyond relationship impasses to build stronger bonds.

“Henry taught me how to ride a bicycle. He taught me how to play baseball. He was tall, handsome and smart. He had friends. He had girlfriends,” says Xavier Amador, PhD, of the brother he always looked up to.“My mother, Henry and I immigrated from Cuba in the late 1960s as refugees,” says Dr. Amador. “Our father was killed during the revolution. We had nothing.”

They made their home in Ohio, where Henry took a job pumping gas at age 13 to help the family.

So when years later, at age 29, Henry changed—becoming a man who could no longer hold a job or keep friends, who hadn’t had a girlfriend in years, who began having delusions that their mother was the devil—Dr. Amador, then 21, confronted him. “I called him selfish, immature and irresponsible because he wouldn’t admit he had a problem. All that history of closeness, of feeling protected, of wanting to be like him went out the window.”

The “aha” moment that changed everything

Seven years went by with the brothers butting heads, going from close allies to bitter adversaries. It wasn’t until Dr. Amador found himself treating a man while working toward his PhD that something clicked.

“The patient was paralyzed on the left side of his body. Yet he insisted he was able to move his arm,” says Dr. Amador. “When I asked him why he wouldn’t show me, he said, ‘I just don’t feel like it.’

“It was the same answer my brother would give me when I’d say to him, ‘Henry, you haven’t had a job. You don’t have friends anymore. You don’t have a girlfriend. Doesn’t that tell you something is different about you?’ ”

Dr. Amador realized that what seemed to be frustrating denial on Henry’s part was actually a neurological symptom. Called anosognosia, “it’s caused by brain lesions that make it impossible for a person to see he’s changed.

“I would never have dreamed of blaming Henry for his hallucinations, yet I’d been blaming him for his inability to see that he was ill,” says Dr. Amador.

Making the LEAP

Once he understood Henry’s denial was actually a symptom he couldn’t control, Dr. Amador took a different tack—which ultimately evolved into the LEAP Institute, a series of techniques that helps loved ones break through similar impasses. Often, these can linger for years, ruining relationships and impeding treatment.

“The first thing I did was apologize to Henry,” says Dr. Amador. “I told him I was sorry for all the years I told him he was mentally ill, and I told him I wanted to help him and be close to him again.”

With that, the brothers stopped fighting the unwinnable battle of “You’re sick!” “No, I’m not” and began to reestablish a trusting relationship. “We were talking again. I wasn’t bringing up his illness or his need for medicine anymore,” recalls Dr. Amador. “I started listening to him, and together we focused on helping him achieve his goals…things like getting a job, finding a girlfriend”

And a curious thing happened. Henry started seeking out his brother’s opinion. He took his medicine. He found a girlfriend. And in the last 18 years of his life, was hospitalized just once—compared with the 30-plus hospitalizations he’d had before their healing reconciliation.

It’s testament to the power of a listening relationship, says Dr. Amador. Sadly, Henry died about five years ago in a car accident, but one thing brings Dr. Amador solace: “I can tell you my brother was happy,” he says. “He embraced the life he had.”

Is it time for you to take the LEAP?

Are you at a relationship impasse? Perhaps a loved one with mental illness is saying he doesn’t need help? Or maybe it’s a friend struggling with substance abuse? The LEAP Institute, which has helped people worldwide, may help you break through, too. Here’s what it stands for

Listen: Let your loved one talk, then calmly reflect back what they are saying to you: “So you’re not sick…”

Empathize: Put yourself in your family member or friend’s shoes and let him know with statements like “I understand what you are trying to tell me.” The idea is to reach out to him where he is at with his experience.

Agree: Find some common ground. For example, maybe he will agree to call you any time he feels the need to drink alcohol.

Partner: Work together on helping your relative or friend achieve certain goals: to be in treatment, to develop work skills, to develop relationship skills. “Once you’ve established a trusting relationship, your loved one will stop pushing back,” says Dr. Amador.

Not only will he seek your opinion, but it will carry far more weight than before. And when he asks, give your opinion gently—e.g., “I think the medicine will help you stay out of the hospital so you can keep your job.”

Returning civility to politics requires taking a ‘LEAP’ | Opinion

Miracles can result when we care for others and listen to them from the heart. Putting these principles into practice takes courage.

Our political divisions, at times, can sully our family relationships and pit neighbors against one another, cause rifts between our elected representatives and lead to stalemate and stagnation. We are urged by our leaders to put our differences aside for the sake of our country.

Imagine a red state, like Tennessee, and a blue state like California. Do we want purple states, in which red and blue merely exist side by side but do not really work together? A physician might diagnose purple in the body as a lack of oxygen, a suffocation of cells, and, if not treated, could lead to death.

The solution, I believe, is as old as the Smokies in Tennessee and the Sierra Nevada in California.

It was presented by author Xavier Amador, a clinical psychologist and professor at Columbia and New York universities, among others, in his book, “I’m Right, You’re Wrong, Now What?” He calls it “LEAP,” which is listen, empathize, agree and partner.

Putting these into practice takes courage. Do we avoid anyone who does not share our beliefs? Even relatives?

Listen

Miracles can result when we care for others and listen to them from the heart.

If we restrain our tendency to interrupt; if we hear them out for as long as they are willing to share; if we repeat back to them the gist of what they have said – without criticism—then we both will know that they have been heard correctly.

They will also know that their views are important to us.

Empathize

While understanding their feelings and desires, we don’t necessarily have to agree with their solutions.

But this is not the time to raise any argument whatsoever.

Not one word.

Agree

Some of what they have said we can agree with.

Be pleased to tell them so.

Partner

If the others recognize that we truly care about them and their opinions, they may be willing to listen to what we have to say.

However, we should not be overly eager to jump in and destroy the fragile relationships we are building. If we patiently wait until the others are really ready to hear from us, they might listen. Because we care, we will want to share our views humbly, carefully, diplomatically and with great sensitivity.

To adapt Amador’s method to our political situation in America, we can begin a conversation with a statement on which 99% of us can agree. I have heard it in many interviews with Donald Trump supporters, And it could be said of Joe Biden supporters as well. “I want what is best for me and my family.”

It goes ahead of education, money, doctrine, race, gender, politics and even international relations.

From there, we can take a great “LEAP.”

At Christmas, many of us celebrate the birth of one who has been called “the Prince of Peace.” This holiday season, we have a perfect, gift-wrapped opportunity to begin this LEAP process.

We can listen within our own families and from there, we can extend it to our in-laws, our neighbors, our co-workers, even our representatives in government.

This is what the framers of our Constitution — a varied group of individuals — had to do. They looked to the future, toward “a more perfect union,” toward a government that would serve them and their families.

“The On Conquering Schizophrenia Project” | Q&A with Dr. Amador

Before ensuing to the interview, please allow me to share a brief story on a “higher” calling, a “noble” calling, and a lasting “legacy”! Sometimes a “calling” nudges, assumes, and ultimately prevails! Renowned clinical psychologist, Dr. Xavier Amador, ever so graciously joins “The On Conquering Schizophrenia Project” for a brief, but essential, four question Q&A. Dr. Amador is an undisputed and unquestionable global leader on schizophrenia, and also on “anosognosia”. Anosognosia is a neurological symptom often found in schizophrenia. Its manifestation presents as a “lack of insight“ into one’s illness. Those with anosognosia do not believe they have a mental illness; this being, despite clinical certitude and despite it being readily apparent to all others, laypersons included.

Dr. Amador founded the “LEAP Institute” and also Co-founded (and sits as current CEO) the “Henry Amador Center on Anosognosia”. Both organizations are devoted to the cause and mission of anosognosia. Prior to founding these leading organizations, Dr. Amador was already highly and exceedingly accomplished, and certainly so! Dr. Amador was a clinical psychologist and a Professor at Columbia University. He was the Director of Psychology for the highly reputable New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI). Further, Dr. Amador was a renowned forensic psychologist and contributed to many high profile cases. And even further yet, Dr. Amador was also on the NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) Board of Directors and was Co-chair for the DSM-IV for the “Schizophrenia and Related Disorders” section. Dr. Amador’s career was certainly highly accomplished, reputed, renowned, and prestigious! But it seems to me, at once, Dr. Amador was then urged by a higher “calling”!

Story told, Dr. Amador’s life was personally touched by schizophrenia. His brother, Henry, at once was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Subsequently, an apparent confluence and serendipity emerged. In his earlier years, while researching schizophrenia, Dr. Amador studied anosognosia. In a parallel fashion, Dr. Amador came to recognize this symptom in his brother, Henry. Dr. Amador, then over a number of years, perfected his knowledge, understanding, and expertise and became the go-to expert in the world on anosognosia. Sooner than later, his expertise on anosognosia helped him to support his brother, Henry, and assisted Henry to an eventual sustained recovery from schizophrenia. I am sure Dr. Amador would would agree, helping his brother was the pinnacle and “highest” of all his “callings”, hands down and most certainly! And yet just further beyond, by manner of another unique confluence, a complimentary “noble” calling also further tugged!

Now a global expert on anosognosia, Dr. Amador decided to leave his numerable prestigious professional positions to dedicate himself to this crucial variable known as anosognosia. With Henry now recovered, Dr. Amador heeded a personal calling and subsequently founded the “LEAP Institute” and Co-founded the “Henry Amador Center on Anosognosia”. Both organizations carry the most “noble” mission to educate society, and all the associated essential players, on this oft obscured but most essential symptom. Personally, I see these organizations, pointed missions included, as parcel to Dr. Amador’s serendipitous and compelling “noble” calling!

Dr. Amador certainly met his calling, beyond and exceedingly so, and through his two organizations now has trained tens of thousands on anosognosia helping troves upon troves of others! Dr. Amador created and developed the LEAP (LISTEN-EMPATHIZE-AGREE-PARTNER) communication methodology to use with those who have schizophrenia who present with anosognosia. By my estimation, Dr. Amador is currently the preeminent expert in the world on anosognosia. Prior to the founding of these two organizations, Dr. Amador was an already highly accomplished clinical psychologist, and in all regards and in all manners! But by my intuitive estimation, he even further transcended!

Lastly, in our story, comes the lasting “legacy”. Dr. Amador’s brother, Henry, while engaged in an altruistic act of kindness of helping a mutual bus passenger exit the bus with her packages, most regrettably and tragically, was killed just outside the bus in a random motor vehicle accident. Dr. Amador says such altruism was part of Henry’s routine caring and kind character! In his tribute, Dr Amador’s organization was named the “Henry Amador Center on Anosognosia”. Henry’s life is a legacy, and undeniably of the highest sort! Henry’s life has bettered and improved the lives of so many, beyond the countable! This, I feel, may be the “highest” of all callings! Thank you, Henry Amador, for your lasting legacy! Your life was truly meaningful and it continues to benevolently resound!

Regarding anosognosia, no one in the world comes with more expertise than Dr. Amador. If you are not familiar with anosognosia, and the topic pertains in some manner to your life, I encourage you to learn more. For starters, you can visit Dr. Amador’s websites and/or grab his books!

Lastly, on a personal note, I want to thank Dr. Amador for his participation! Prior to my inquiry for his interview, I have no doubt he had an already full and capable hopper! For a person of such terrific repute, his kindness easily matches and exceeds! His participation is heartily appreciated, and I add a full bucket more to the catch! And so it is, without further ado, please now allow me to introduce to you the ever iconic, Dr. Xavier Amador!

After the interview, at the very bottom, please find three links to Dr. Amador’s websites and book. Also, please see the attached image at very bottom for some further brief highlights of Dr. Amador’s career and accolades!

BEGIN Q AND A-

Q: Dr. Amador, in the mental health professions, you are a leading voice in the world including on the variable known as anosognosia, that being as defined, a “lack of insight” into one’s illness (inclusive of schizophrenia). Regarding anosognosia and its implications in schizophrenia, par excellence Dr Amador, you have written a national bestseller “I Am Not Sick, I Don’t Need Help!“ (with 1.5 million copies sold), you founded and direct the seminal, innovative, and highly reputed “LEAP” Institute (a training center with dedication to anosognosia), you TedTalk(ed) on its topic (over 200K views), you have made numerous media appearances including at times clarifying on anosognosia, and you actively and internationally lecture and train on anosognosia. From my estimation, Dr. Amador, anosognosia is a primary discernment in the conceptualization and treatment of schizophrenia. Being a global leader in psychology, Dr. Amador, including on anosognosia, can you please give us a description of anosognosia (in schizophrenia) and how its recognition and understanding can ultimately improve clinical outcomes?

People with schizophrenia and related disorders like bipolar disorder frequently appear in denial. As it turns out, denial is rarely the problem. Instead, such persons have another symptom of their mental illness called anosognosia (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, American Psychiatric Press, 2013). Anosognosia is a neurocognitive symptom involving the pre-frontal and frontal lobes. Like delusions and hallucinations, anosognosia is a core feature evident in about half of all persons diagnosed with schizophrenia and related psychoses. In the majority of patients it tends to be stable and not responsive to treatment.

Importantly, this symptom is the top predictor of who will refuse medication and if they are on it, stop taking it. It also predicts an increase in the number of involuntary hospitalizations, a poorer course of illness and poorer psychosocial functioning. As such, this symptom of unawareness of illness is a huge problem and professionals need to assess and diagnose anosognosia in their patients so they can adjust their psychotherapeutic approach to such patients and provide appropriate delivery of medication (i.e., long acting treatments given by injection).

Q: In your opinion, Dr. Amador, based on our current scientific knowledge, is anosognosia a binary yes/no distinction, or is anosognosia present on a sort of spectrum?

Well replicated research is clear, anosognosia is generally present or not. That said, it presents differently in different people. Because it involves more than unawareness of an illness and includes unawareness of signs and symptoms, there are a number of things a person can be unaware of. Consequently we see patients with anosognosia who have “pockets of awareness.” For example, someone who has anosognosia for his mental illness for a decade (he is unaware he has any mental health problem) can nevertheless be aware that the hallucinations he experiences are just that: false perceptions.

Q: Dr. Amador can you please explain how the presence of anosognosia shifts the treatment paradigm away from delusional refutation, or a challenging sort of reality-testing, to a directive that focuses on “motivational interviewing” and engagement? Dr. Amador, how would you engage with somebody with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who has anosognosia?

So how do we help someone who has anosognosia? How do we help someone who is absolutely certain that nothing is wrong with them and think that everybody who is trying to help them is dead wrong? Like the science on anosognosia, the research on how to help is enlightening.

My colleagues and I conducted research on a program I developed called LEAP (Listen, Empathize, Agree, Partner). Using LEAP you first learn to stop doing much of what you’ve been doing! I had to go through this when talking to my brother who had schizophrenia, anosognosia, and refusal of all help (including medications). What did I stop doing? I realized that I was doing the same thing over and over again—telling him he was ill and needed help—and expecting a different result. According to Einstein’s definition of insanity, I was insane! I was not harsh with myself because I was doing what any loving brother would try to do for a mentally ill loved one. I was trying to prove to him that he was ill and needed to see a psychiatrist. But with every attempt he pushed back and moved further and further away from accepting any kind of help. I learned to stop telling him he was sick and needed drugs. That is the cornerstone of the LEAP approach. That, and focusing my efforts on listening to him, being empathic and building a relationship in which he felt truly respected and not judged. I even apologized for all the times I told him he was ill and needed treatment. I then promised him I would never do that again. I kept that promise. The result of my focus on the relationship—instead of focusing on his developing insight—was that he accepted a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication which he took for the rest of his life (18 years). He did not die from his illness. He died in a car accident while helping a pedestrian “safely” on a sidewalk.

Q: Dr. Amador, in your opinion, where do we stand in regards to mental health professionals being aware of the variable known as “anosognosia”? Is more ground yet to be gained, and if so, beyond your own efforts, what do you think it’ll take to get the message out?

We are far from where we should be. There is a natural gap between science and practice. The science on anosognosia is clear yet most practitioners are, no pun intended, unaware of this symptom. We have made progress. The mission of the nonprofit Henry Amador Center on Anosognosia is to train professionals and the lay public about this serious symptom of mental illness. Slowly but slowly I have seen a change. Indeed, just last week the parents of a young man with schizophrenia said they had received his discharge summary from the hospital and in it he had been diagnosed with “Schizophrenia with anosognosia.” As for getting the word out, supporting organizations like the nonprofit just mentioned above will help. And talking about it with whomever will listen. That is why I am so happy to have participated in this interview.

END Q AND A—

With much gratitude, I thank Dr. Amador for his participation in “The On Conquering Schizophrenia Project”! I truly appreciate Dr. Amador’s given time, unmatched expertise, and easy kindness! He is a certain legend!

Below, by manner of three links, please find some of Dr. Amador’s websites and work (including his national bestselling book). If you care to learn more on anosognosia, Dr. Amador’s work will educate and inform like none other! Also, the attached image below briefly expounds a few further highlights on Dr. Amador’s brilliant achievements and professional credits!

I also want to truly thank all the readers of this interview! I hope an item was fruitful! But, so it is for now, my dear reader, we briefly depart. In the meanwhile, I extend to you, and yours, all the best of times and the very best of dispositional spirits! —Robert Francis, LCSW

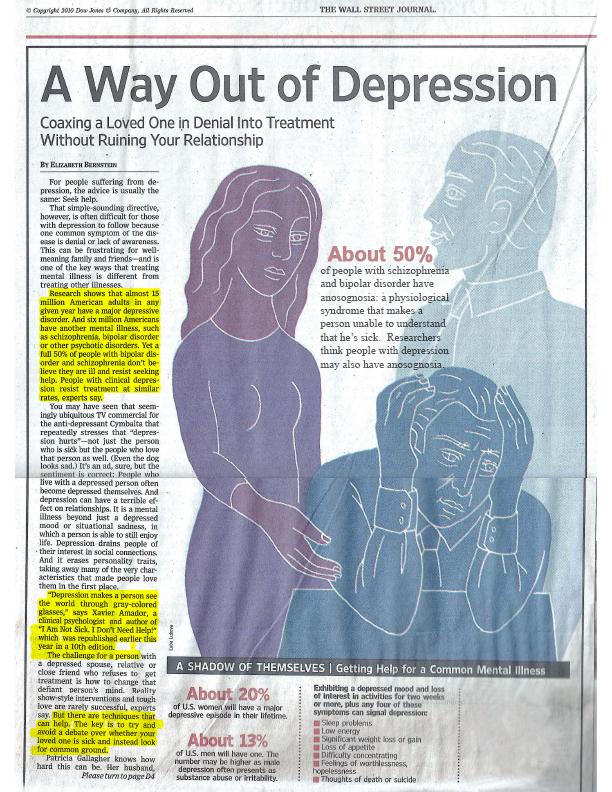

Why it’s often hard for people to recognize their own mental illness

By

If someone was telling you to take insulin but you didn’t think you had diabetes, you probably wouldn’t take the medication, right?

That’s how Bob Krulish explains anosognosia, a tricky condition that accompanies some mental illnesses.

Krulish is a mental health advocate with a local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness based on the Eastside and an author who has made it his life’s mission to teach and work with families affected by anosognosia.

Anosognosia (pronounced uh-nah-suh-no-zhuh) is a neurological impairment that affects an estimated 30% of people with schizophrenia and 20% with bipolar disorder, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, though others believe the percentage may be much higher. Ultimately, anosognosia makes it hard for people with mental illness to have insight into their diagnosis or be aware of it.

Krulish suggests that rather than arguing or reasoning with a person with severe mental illness who’s refusing treatment, that family members and friends instead use a method called LEAP: listen, empathize, agree and partner. It’s a program started by Dr. Xavier Amador, a clinical psychologist who researches and writes about anosognosia.

Instead of proving to the person that something is wrong, clinicians and family can focus on goals both parties agree to, such as wanting to be discharged or keeping a steady job. That can build trust, strengthen relationships, and ultimately improve outcomes for the person with mental illness, Krulish said.

“My whole process is about evoking from the individual what their reasons might be for being on medication, what their reasons might be for behaving differently, what their goals might be,” Krulish said. “I’d much rather see it be internally motivated than externally forced upon them.”

Tips for talking to a loved one about their mental illness:

- Educate yourself. Learn as much about the mental illness your loved one has.

- Listen with empathy and reflectively. Do not try to reason or prove to the person that they have a mental illness or insist they take their medication. Instead, take time to build a trusting relationship. Only give your opinion when asked.

- Focus on goals both you and the other person may want. For example, custody of their children, or a steady job or relationship.

- Consider making a psychiatric advance directive, a legal document that explains what kinds of future mental health treatment a person may want. Also consider naming a trusted individual to make those treatment decisions.

Source: Henry Amador Center for Anosognosia, National Alliance on Mental Illness

If a loved one with mental illness or addiction is refusing treatment, Dr. Xavier Amador, author of “I Am Not Sick, I Don’t Need Help!” offers proven techniques to help your loved one accept the treatment they need. Read the full article here.

How to Help Someone with Mental Illness Accept Treatment