Anosognosia: The Root of the Problem

Understanding Anosognosia: First Hand Experiences

Dr. Amador’s research on anosognosia and poor insight was inspired by his success helping his brother Henry, who developed schizophrenia, accept treatment. Like tens of millions of others diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar and substance abuse disorders, Henry did not believe he was ill. Unfortunately, this lack of insight into serious mental illness is not uncommon.

A Clinical Discussion About Matt

Sitting around the table with me were two nurses, a therapy aide, a social worker and a psychiatrist. We were in the middle of our weekly clinical team meeting discussing whether we thought Matt was well enough to be discharged from the hospital. “His symptoms have vastly improved,” began Maria, his primary nurse. “The hallucinations have responded to the medication. He’s calmer and no longer paranoid.”

“Both his mother and father are ready to have him come home again,” added Cynthia, Matt’s social worker, “and Dr. Remmers has agreed to see him as an outpatient.”

“Sounds like we’ve got all our ducks lined up in a row.” Dr. Preston, the team leader, capped the discussion and scribbled a note in Matt’s medical chart.

“Only one thing troubles me,” Cynthia interjected hesitantly. “I don’t think he’s going to follow through with the treatment plan. He still doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with him.”

“He’s taking his medication,” I observed.

“For now. But he’s really stubborn and so defensive. I don’t think that will last more than a week or two after he hits the sidewalk.”

I had to agree with Cynthia’s prediction, but I didn’t share her view as to why he wouldn’t take his medication on the outside.

“What makes you say he’s defensive?”

Nearly everyone around the table burst out laughing, thinking I was being facetious. “No, really, I’m serious,” I said.

Dr. Brian Greene, the resident assigned to the case, jumped into the discussion.

“Well, he doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with him. As far as Matt’s concerned, the only reason he’s here is because his mother forced him into it. The man is full of pride and just plain stubborn. Don’t get me wrong—I like him, but I don’t think there’s anything else we can do for him as long as he’s in denial. No one’s going to convince him that he’s sick. He’s just going to have to learn the lesson the hard way. He’ll be back before he knows what hit him.”

Dr. Preston, recognizing that Matt’s discharge was a forgone conclusion, ended the discussion. “You’re probably right about that and about the fact that there’s nothing more we can offer him here. When he’s ready to stop denying his problems, we can help. Until then, our hands are tied. Brian, you’re meeting with Matt and his parents at three o’clock to go over the plan. Any questions?” After a moment’s silence, Matt’s medical chart was passed around the table for each of us to sign off on the discharge plan.

My Brother’s Illness

During the first few years of my brother’s illness (before I went to graduate school to become a clinical psychologist), I often thought he was being immature and stubborn. Asked about what his plans were after being discharged from yet another hospitalization, he ritually answered, “All I need to do is get a job. There’s nothing wrong with me.” His other stock answer was, “I am going to get married.” Both desires were natural and understandable—but unrealistic given his recent history, the severity of the illness, and his refusal to accept treatment. Someday, perhaps, he would realize his desires, but it was very unlikely unless he was actively involved in the treatment recommended by his doctors.

It was exasperating to talk to Henry about why he wasn’t taking his medication. Having limited experience with the illness, the only reason that I could think of for his adamant refusal was that he was being stubborn, defensive, and—to be frank—a pain in the rear. I was lucky that I thought of my brother only as being stubborn because, like many children of people with serious mental illness, Anna-Lisa often wondered if her mother didn’t love her enough to want to get better. It took her mother’s suicide to educate Anna-Lisa about what was really happening. And, for myself, it was only after I started working in the field and met many more people with serious mental illness that I stopped giving such theories much credence. It just never made sense to me that the pervasive unawareness and odd explanations given by people like Matt and my brother could be explained simply as having an immature personality or a lack of love.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Let’s look at the research for a more objective answer to the question of what causes poor insight and refusal to accept treatment.

The Mystery of Poor Insight

Three Potential Causes

I have considered three possible causes of poor insight in the seriously mentally ill. First, it could stem from defensiveness—after all, it makes sense that someone who is seriously ill would be in denial about all the potential and promise for the future that has been taken by the disease.

Or, perhaps it’s simply the result of cultural or educational differences between the mentally ill person and the people who are trying to help him. Differences in subculture and values are often blamed. For example, Anna-Lisa always believed that her mother’s poor insight wasn’t denial so much as a preference for the interesting and fantastic world her illness provided her. When she was symptomatic, the world was a magical place filled with adventures to be had and mysteries to explore. As a result, Anna- Lisa never wanted to question her mother’s delusions, because she feared that by talking about them, she might take them away and somehow cause her mother even more pain.

The third possible cause is that poor insight into the illness stems from the same brain dysfunction that is responsible for other symptoms of the disorder. Historically, psychoanalytic theories predominated to explain poor insight in schizophrenia. The literature is rich with case studies suggesting that poor insight stems from defensive denial, but the question had never been tested in controlled studies until recently.

Two of my doctoral students, Chrysoula Kasapis and Elizabeth Nelson, took different approaches to this question in their thesis research. Dr. Kasapis examined the overall level of defensiveness in the patients she studied, while Dr. Nelson looked at the issue of stigma.

Neither approach to the question found anything of significance. Highly defensive patients were generally no more likely to have poor insight than those with little or no defensiveness. Similarly, how stigmatizing patients perceived their symptoms to be had little effect on insight into their illnesses. Everyone gets defensive from time to time and some are more prone to denial than others—the same holds true for people with serious mental illness. However, “everyday” defensiveness is not responsible for the gross deficits in insight that are so common in these patients. Cultural differences between the examiner and patient may also play a role in the mislabeling of someone as having poor insight. In other words, a patient may be well aware of most, if not all, aspects of his mental illness, but his subculture might label it something else. Consequently, he would not use the label “mental illness” to describe himself. He might say instead, “I have a nervous problem,” or, in the case of religious beliefs such as those common to some Caribbean countries, “I am possessed by evil spirits.” The subculture of the afflicted person needs to be considered in any study of insight.

Related to the issue of cultural influences is the question of patient education. Has the patient ever been told that he or she has an illness? If so, has he or she been taught how to identify and label symptoms of the disorder? In my experience, most patients with poor insight have been told about the illness they have, yet either claim they haven’t been told or adamantly disagree, claiming that their knowledge is superior to that of the doctors making the diagnosis. It’s ironic, but many patients with poor insight into their own illnesses are excellent at diagnosing the same illness in others!

The answer to the question of whether half of all people with serious mental illness don’t know they are ill because they have no information about the illness is actually obvious when you step back for a moment. If you had heartburn that was bad enough for a friend or relative to convince you to see your family doctor, who then diagnosed the problem as heart disease and explained that the pain was angina, you would stop referring to the pain as heartburn and start calling it angina. You would respond by making an appointment with a cardiologist and canceling your next visit with the gastroenterologist.

Why, then, do so many people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder fail to do this? Why do they persist in calling their pain “heartburn” despite all evidence to the contrary?

Anosognosia: A Concept of Self that is Stranded in Time

In our paper published in 1991, my colleagues and I proposed that poor insight in people with serious mental disorders is a consequence of, to coin a phrase, “a broken brain.” We came to believe that pervasive lack of insight and the accompanying illogical ideas offered to explain being hospitalized stemmed from neurological deficits. At that time, we hadn’t yet considered a neurological hypothesis to explain poor insight in bipolar disorder, but we felt there was good reason to believe that what we were seeing in patients with schizophrenia was a consequence of brain dysfunction rather than stubbornness, defensiveness, or ignorance about mental illness in general. The fact is that the brain circuitry responsible for recording and updating self-concept is not working properly in such patients.

For instance, my self-concept includes the following beliefs about my abilities: I can hold down a job; if I went back to school, I would be a competent student; I have the education and experience to be a therapist; and I am generally socially appropriate when I interact with others.

What are some of the beliefs you hold about yourself and your abilities? Do you believe that you can hold down a job? What if I told you that you were wrong, that you were incapable of working and might never find employment unless you swallowed some pills I had for you? And that you would have to take those pills for a very long time, possibly for the rest of your life?

What would you say to that? Probably the same thing my brother once said to me when I told him he would never hold down a job again unless he took his medication faithfully: “You’re out of your mind!”

You would likely think I was joking, and after I convinced you that I was dead serious, you would come to believe I was crazy. After all, you know you can work—it’s an obvious fact to you. And, if I involved other people, including relatives and doctors, you might start to feel persecuted and frightened.

That is exactly the experience of many with serious mental illness whom I have interviewed. Their neuropsychological deficits have left their concepts of self—their beliefs about what they can and cannot do—literally stranded in time. They believe they have all the same abilities and the same prospects they enjoyed prior to the onset of their illnesses. That’s why we hear such unrealistic plans for the future from our loved ones.

If a Man Can Mistake his Wife for a Hat…

If you have never talked to someone who has suffered a stroke, brain tumor, or head injury, what I have just said might seem difficult to believe. If so, I recommend that you read The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, written by the late neurologist Oliver Sacks (also the author of the book upon which the movie “Awakenings” was based). Dr. Sacks had the gift of being able to describe, in vivid detail, the inner life of people who have suffered brain damage.

Writing about the case which gave title to his book, Dr. Sacks described a man who had cancer in the visual parts of his brain and noted that when he first met Dr. P., this music professor couldn’t explain why he’d been referred to the clinic for an evaluation. He appeared normal—there was nothing unusual about his speech—and he displayed high intelligence. As the neurological evaluation proceeded, however, bizarre perceptions emerged. When asked to put his shoes back on, he delayed—gazing at his foot with intense but misplaced concentration. When Dr. Sacks asked if he could help, Dr. P. declined the offer and continued looking around. Finally, he grabbed his foot and asked, “This is my shoe, no?” When shown where his shoe actually was, he replied, “I thought that was my foot.”

There was nothing at all wrong with Dr. P.’s vision—it was the way his brain was constructing and categorizing his perceptions that was disturbed. Later, when he was sitting with his wife in Dr. Sacks’s office, he thought it was time to leave and reached for his hat. But instead of his hat, he grabbed his wife’s head and tried to lift it off. He had apparently mistaken his wife’s head for a hat! When giving talks about poor insight in serious mental disorders, I often like to say, “If brain damage can cause a man to mistake his wife for a hat, it is easy to imagine how it can cause someone to mistake his past self for his current self.”

In the late 1980s, I worked extensively with neurological patients, administering psychological tests designed to uncover the deficits caused by their brain damage. I couldn’t help noticing the similarities between the neurological syndrome called anosognosia (i.e., unawareness of deficits, symptoms, or signs of illness) and poor insight in persons with serious mental illness. Anosognosia bears a striking resemblance to the type of poor insight we have been discussing. This resemblance includes both symptomatic and neurological similarities.

Strange Explanations

For example, patients with anosognosia will frequently give strange explanations, or what neurologists call confabulations, to explain any observations that contradict their beliefs that they are not ill. One 42-year-old man I evaluated had been in a car accident and had suffered a serious head injury that damaged tissue in the right frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes of his brain, leaving him paralyzed on the left side of his body. When I met with him about a week after the accident, I asked if he could raise his left arm for me and he answered “yes.” When I asked him to do it, he lay there expressionless, unable to move his paralyzed arm. I pointed out that he had not moved his arm. He disagreed. So, I asked him to do it again while looking at his arm. When he saw that he could not move his arm, he became flustered. I asked him why he did not move it, and he refused to answer at first. When I pressed him, he said, “I know this is going to sound crazy, but you must have tied it down or something.”

Anosognosia has been with us for as long as our species has enjoyed the benefits of consciousness. More than 2,000 years ago, L.A. Seneca, writing on the moral implications of self-beliefs, described what appears to be a case of anosognosia following hemianopia (blindness caused by brain damage): “Incredible as it might appear…She does not know that she is blind. Therefore, again and again, she asks her guardian to take her elsewhere. She claims that my home is dark.” How could someone not realize she was blind? And why, when faced with the evidence, would she seek to explain away the blindness?

The man who had been paralyzed in the car accident could not understand that he could no longer move the left side of his body.

It didn’t fit with what he believed about himself (that his arm and leg worked fine), so he couldn’t help trying to explain away any evidence to the contrary. He was just like the blind woman who did not understand that she was blind—and more easily believed an alternative explanation than the truth (e.g., the house was dark). Every day, someone with a serious mental illness utters similar explanations to buttress his belief that there is nothing wrong with him. When one’s conception of who one is gets stranded in time, cut off from important new information, one can’t help ignoring or explaining away any evidence that contradicts it. As a result, many chronically mentally ill persons attribute their hospitalizations to fights with parents, misunderstandings, etc. Like neurological patients with anosognosia, they appear rigid in their unawareness, unable to integrate new information that is contrary to their erroneous beliefs.

One final similarity between neurological patients with anosognosia and the seriously mentally ill involves the patch-like pattern of poor insight. Pockets of unawareness and awareness often coexist side by side. For example, the anosognosia patient may be aware of a memory deficit but unaware of paralysis. Similarly, we have seen many patients with schizophrenia who are aware of particular symptoms while remaining completely unaware of others.

Neurological Damage

Damage to particular brain areas can result in anosognosia. Studies of anosognosia, therefore, provide a practical starting point for hypothesizing about the brain structures responsible for insight in persons with serious mental disorders. Neurological patients with anosognosia are frequently found to have lesions (i.e., damage of one kind or another) to the frontal lobes of their brains. Interestingly, research has shown that these same areas of the brain are often dysfunctional in people with serious mental illness.

In one study of neurological patients at Hillside Hospital in Queens, New York, conducted in collaboration with Dr. William Barr and Dr. Alexandra Economou, I compared patterns of unawareness in three groups of patients suffering damage to three different regions of the brain. This study was funded by the Stanley Foundation and had as one of its goals identifying the brain dysfunction most likely to produce awareness deficits. As expected, patients with frontal lesions were more likely to show problems with insight into their illnesses than patients with left posterior damage. Let’s look at an example.

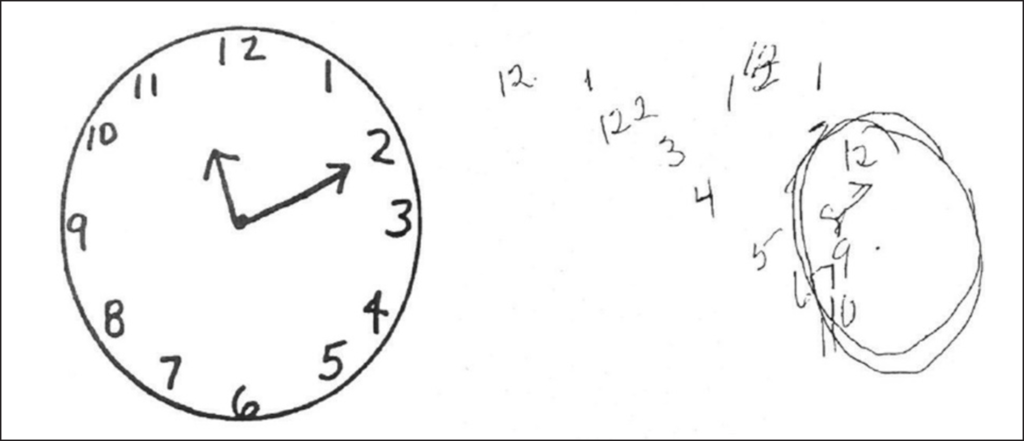

George, a 71-year-old man who had suffered a stroke, was asked to draw the clock on the left side of the figure that appears below. Before drawing the clock, he was asked, “Do you think you will have any difficulty copying this picture?”

George was instructed to use the following 4-point scale to answer the question: 0 = no difficulty, 1 = some difficulty, 2 = much difficulty, and 3 = cannot do. He answered “0” and said he would have no difficulty. The right side of the figure shows the drawing he made after exerting great effort.

More striking than his inability to recognize that the stroke had left him unable to perform such a simple task was what happened next. When asked if he’d had any difficulty drawing the clock, he answered, “No, not at all.” Further questioning revealed that he could not see or comprehend the differences between his clock and ours.

When it was pointed out to him that his numbers drifted past the circle, he became flustered and said, “Wait, that can’t be my drawing. What happened to the one I drew? You switched it on me!” This is an example of a confabulation. Confabulations are the product of a brain “reflex” that fills in gaps in our understanding and memory of the world around us. Almost everyone confabulates a little—you’ve heard people stop in the middle of recounting something that happened to them and say something like, “Wait, I was lying. I don’t know why I said that. It didn’t happen that way!” This is an example of an instance when someone realizes he has confabulated and corrects himself. Confabulations are “constructed” memories and/or experiences that are especially common in people with brain dysfunction. However, in such individuals, we don’t usually observe self-correction, because they don’t understand the need for correction. George wasn’t lying when he said I had switched the drawing on him. It was the only thing that made any sense to him, so for a moment, he believed that was what had happened.

In his book The Principles of Psychology, William James wrote: “Whilst part of what we perceive comes through our senses from the object before us, another part (and it may be the larger part) always comes from our own mind.”

There are few better examples of James’s insight than the one I have just given you. George “saw” his drawing using his sense of vision. But his perception of the clock—the image of the drawing that was processed in his brain—was something altogether different from what his eyes saw. George had a concept of himself, a self-schema, that included the belief that he could easily copy a simple drawing of a clock.

Your Self-Schema

You have the same belief as part of your self-schema. You might not consider yourself artistically endowed, but you believe that you could produce a reasonable facsimile of the drawing if asked to. In a sense, this belief was stranded in George’s brain, disconnected from his visual senses and left unmodified by the stroke he had suffered. He was operating under beliefs that were linked to his past self rather than his current self. He saw the numbers drifting outside his lopsided circle, but he perceived the numbers to be in their proper place inside a symmetrical circle.

Our brains are built to order, and even help construct, our perceptions.

Here is a simple example of what I am talking about. Answer this question: What letter appears in the box you see here?

If you answered “E” you saw what the majority of people who are given this task see. But in reality, you did not see the letter E. What you saw is a line with two right angles (a box-like version of the letter “C”) and a short line that is unconnected to the longer one. You likely answered “E” because you perceived the letter E. The visual processing and memory circuits of your brain “closed the gap” between the lines so you could answer the question.

To prove that poor insight in serious mental disorders is neurologically based, however, my colleagues and I needed more than observed similarities with neurological patients. We needed testable hypotheses and data that were confirmatory.

Knowing that patients with schizophrenia frequently show poor performance on neuropsychological tests of frontal lobe function, we hypothesized that there should be a strong correlation between various aspects of unawareness of illness and performance on those tests. Dr. Donald Young and his colleagues in Toronto, Canada, quickly tested and confirmed our hypothesis. They studied patients with schizophrenia to examine whether performance on neuropsychological tests of frontal lobe function predicted the level of insight into illness, and the result showed a strong association between the two. Of particular note is the fact that this correlation was independent of other cognitive functions they tested, including overall IQ. In other words, poor insight was related to dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain rather than to a more generalized problem with intellectual functioning. Taken together, these results strongly support the idea that poor insight into illness and resulting treatment refusal stem from a mental defect rather than informed choice.

But just as one swallow does not make a summer, one research finding does not make an indisputable fact. The next step in determining more definitively whether poor insight into illness is a consequence of frontal lobe dysfunction is to replicate the findings of Young and his colleagues in a new group of patients.

Further Examples in Research

As it turns out, the finding that poorer insight is significantly correlated with frontal lobe dysfunction (and reduced grey matter in the frontal lobes) has been replicated many times by various research groups (see table below). The list of replications I give here will undoubtedly be added to by the time you read these words.

Repeated replications by independent researchers are infrequent in psychiatric research, so the fact that various researchers have found essentially the same thing as Young and his colleagues speaks to the strength of the relationship between insight and the frontal lobes of the brain. A few studies have not found this relationship, but in those cases methodological flaws in the design of the research are likely the reason.

Executive (Frontal) Dysfunction and Poor Insight

- Young et Schizophrenia Research, 1993

- Lysaker et al. Psychiatry, 1994

- Kasapis et Schizophrenia Research, 1996

- McEvoy et Schizophrenia Bulletin, 1996

- Voruganti et Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 1997

- Lysaker et Acta Psychiatr Scand, 1998

- Young et al. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1998

- Bell et Chapter in: Insight & Psychosis, Amador & David, Eds. 1998

- Morgan et Schizophrenia Research, 1999a & 1999b

- Smith et al. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1999

- Smith et Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2000

- Laroi et al. Psychiatry Research, 2000

- Bucklet et al. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 2001

- Lysaker et Schizophrenia Research, 2003

- Drake et Schizophrenia Research, 2003

- Morgan and David (review) in Insight and Psychosis, 2nd Edition (Oxford University Press, 2004)

- Keshavan et Schizophrenia Research, 2004

- Aleman et al. British Journal of Psychiatry, 2006

- Pia & Tamietto, European Archives of Psychiatry and Clini- cal Neuroscience, 2006

- Shad et , Schizophrenia Research, 2006

- Sartory et Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2009

- Bora Schizophrenia Research, 2017

- Asmal et Schizophrenia Research, 2017

Anatomical Brain Differences and Poor Insight

There is also an emerging body of literature linking poor insight in schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses to functional and structural abnormalities in the brain, usually involving the frontal lobes (e.g., the Asmal et al. study above). For example, evidence from brain imaging and post-mortem studies find differences in the brains of schizophrenia patients who have insight or awareness of illness, when compared to those who do not.

From 1992 to 2017, 22 studies compared the brains of individuals with schizophrenia, with and without awareness of illness. All but two studies found significant differences (between aware and unaware subjects) in one or more anatomical structures. A variety of anatomical structures were involved—including the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, medial frontal cortex, and inferior parietal cortex. Three of the above studies included individuals with schizophrenia who had never been treated with medication, discounting the hypothesis that these brain differences resulted from treatment. A more detailed review of these and other brain-imaging studies (e.g., using MRI, CT and PET scans) can be found in Insight and Psychosis, Amador XF and David AS (Editors), Oxford University Press, 2005.

The research discussed above and other newer studies that link poor insight to structural brain abnormalities lead us to only one conclusion. In most patients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, deficits in insight and resulting non-adherence to treatment stem from a broken brain rather than stubbornness or denial.

Anosognosia and our Authoritative Diagnostic Manuals (i.e., the DSMs)

If you are dealing with a mental health professional who is holding on to the outdated idea that severe and persistent problems with insight are a consequence of “denial” (i.e., a coping mechanism), ask him or her to look at the “Schizophrenia and Related Disorders” section of the DSM-IV-TR. This is the grey- colored DSM most clinicians have. Ask them to read page 304:

Associated Features and Disorders

“A majority of individuals with Schizophrenia have poor insight regarding the fact that they have a psychotic illness. Evidence suggests that poor insight is a manifestation of the illness itself rather than a coping strategy… comparable to the lack of awareness of neurological deficits seen in stroke, termed anosognosia.”

Now, if the person you are trying to educate is extremely resistant and a careful reader, he or she may say something like, “Yes, but I also see that Dr. Amador was the co-chair of this section of the DSM, so he just wrote what he already believes. It doesn’t prove anything!”

If that happens, have the person read the introduction to this revision. He will learn that every sentence in this version of the DSM had to be peer-reviewed before it was added. Peer review in this context involved other experts in the field receiving the proposed text along with all the research articles that supported the changes my co-chair and I wanted to make. All changes had to be supported by reliable and valid research findings.

So, although the field has been slow to give up outdated theories about poor insight in these disorders (thinking it’s denial rather than anosognosia), we are making progress.

But what about the most recent edition of the DSM published in 2013? This is the copy (purple cover) of the DSM currently in widespread use. Here is what the DSM 5 has to say about “poor insight” in schizophrenia (on page 101):

Associated Features and Disorders

“Unawareness of illness is typically a symptom rather than a coping strategy. It is comparable to the lack of awareness of neurological deficits following brain damage, termed anosognosia… This symptom is the most common predictor of nonadherence to treatment. It has been found to predict higher relapse rates, increased number of involuntary treatments, poorer psychosocial functioning, aggression, and a poorer course of illness.

Anosognosia versus Denial

Often, I am asked the question: “How can I know whether I am dealing with anosognosia versus denial?” There are three main things you should look for:

- The lack of insight is severe and persistent (it lasts for months or years).

- The beliefs (“I am not sick,” “I don’t have any symptoms,” ) are fixed and do not change even after the person is confronted with overwhelming evidence that they are wrong.

- Illogical explanations, or confabulations, that attempt to explain away the evidence of illness are common.

Ideally, you would also want to know if neuropsychological testing revealed executive dysfunction. But regardless of whether the problem is neurologically based or stems from intractable defensiveness, or both, the most important question is: How can you help this person to accept treatment? That is the focus of the rest of this book.

Remember, the cause of the severe and persistent “denial” may be less important than how you choose to deal with it. The fact that the person you’re helping does not see what you see and, his or her belief cannot be changed, is all you need to know to move forward.

For more about this story, please see Dr. Amador’s book, I Am Not Sick, I Don’t Need Help!®